Dear Editor,

I read the recent letter submitted by five persons attached, in one way or another, to the University of St. Maarten on “Why Greece should matter to St. Maarten”. For some time, I had been mulling penning such a letter focusing on the lessons that could be learnt using any similarities between the two situations. I want to be clear from the start that I do not wish to create a battle of opinions and this letter is not meant to create an either or situation. I hope to add to what the team led by Dr. Francio Guadeloupe wrote, because I agree with much of what is in that letter.

Before dealing with my original points, there is a need to make some corrections to a few points in the university professors’ letter. First, Jeroen Dijsselbloem is still the Dutch Minister of Finance. He did not need to resign that post in order to become Chairman of the Eurozone group. What he has done is requested that State Secretary Wiebes speak on behalf of the Dutch delegation at meetings. Second, the Eurozone is not an informal club. It is a formally constituted body that is governed by treaties and that possesses formal institutions, the chief one being the European Central Bank. Those corrections made, I wish to add two reasons to why Greece should matter to St. Maarten. These two reasons, namely the importance of sustainability of public finances and the importance of understanding the position of a discussion partner are closely linked.

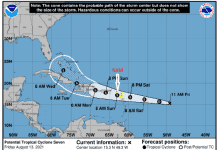

The situation in Greece also concretely teaches us that government finances should be made sustainable. The Eurozone has, in all its discussions with Greece, hammered on the point that cuts and reforms are necessary in order to ensure that Greece can sustain the services it offers to its citizens. The Board of Financial Supervision (CFT) has hammered that St. Maarten too must seek to ensure that its budget and overall financial management are done in such a way that services can be sustained for present and future generations. In both cases, oversight of the budget and its execution is a continuous project and I think a key element of that is a strong statistical agency that monitors the effect of government spending. In the agreement with Greece it has been stipulated that Greece will improve its statistics infrastructure. I see a need to do this in St. Maarten as well as data can help to drive policy making.

As an example, Greece is being “forced” into pension reform because it did not act quickly enough in the face of an aging population. St. Maarten has yet to face that challenge, but we’ve been warned that could become a challenge in the future. If we review the numbers, follow the technocratic advice to reform now and explain it well, the messaging could be simple and palatable to society. If we wait then messaging becomes even more difficult. I think what many are ignoring is that Greece is in quite dire straits. When a government arrives at its lender(s) of last resort, cushioning the blow to society with nice words is not the goal; the goal is ensuring that the government is able to reduce debts by paying off creditors and generating more income. An extreme situation requires extreme measures to solve it and I doubt that any amount of warmth can cushion the blow of someone being told years of inadequate monitoring and reform are the reason they are seeing a drastic reduction or loss of their benefits.

I think it is also necessary to critically examine the causes of debt. Is the debt because we’re attempting to live beyond our means? How did Government build up any particular debt? How does this debt impact the sustainability of the creditor, especially when the creditor has a social function? How do we reform the system to potentially lessen the contribution of government to those creditors moving forward? I miss debate on these questions – maybe because I live outside of St. Maarten.

The situation with Greece also concretely teaches us that we should become very aware of the political motives behind the positions taken by a negotiation partner. From time to time when the budget comes up we hear in political and social circles that it is unfair that the Netherlands “forces” St. Maarten – a developing country – to have a balanced budget. I think this position fails to sufficiently appreciate that by 2007, when the now (in)famous Final Declaration (Slotverklaring) was signed, the euro and the accompanying agreements on fiscal policy for Eurozone members were an entrenched part of the Dutch political landscape.

Because of the agreements made on especially the three percent debt norm in Europe, the Netherlands was already on course to make budget cuts and it is understandable that it would want to take the other countries in the Kingdom along, because of the lessons it had learned. If we look at the position as it stands today, the Netherlands has cut its budget, reformed key areas like social security benefits, reformed education, including changing its formerly part loan/part grant study financing system into a complete loan, and become a “hardliner” on fiscal discipline in talks with its European partners, who are sovereign nations. I think it is also important that we understand that the faction leader of the VVD party in parliament Halbe Zijlstra and Prime Minister Mark Rutte have made a mantra of the statement, “We can’t keep giving out more than we take in.

” Based on these facts, can we really expect that the Dutch approach to St. Maarten, or any other Kingdom partner, would be one where massive debts are allowed? I think it would be illogical to answer yes, especially since it appears that after 15 years of the Euro and the accompanying fiscal rules the Netherlands is seeing successes in the form of a faster reduction of the national debt and the beginnings of new economic growth post the financial and economic crisis of 2008. I honestly think that if people in Philipsburg had a deeper understanding of how decisions are made in the Hague, the types of strategies employed would change. Concretely, I don’t think pleading for, for example, eliminating the balanced budget requirement is going to work, not when the country that you’re negotiating with is actively reducing it budget deficits.

I think the question that hangs in the air after I read the letter by Dr. Guadeloupe is: How do politicians couch these points in socially palatable terms? How do politicians explain to the population that goals you wish to accomplish are potentially beyond your means in the period you wish to implement them? Here in the Netherlands, the governing parties – VVD & PVDA – and the “friendly” opposition who have supported past budgets – D66, Christian Union and SGP – have developed the mantra: “Budget cuts hurt, but …”. I don’t know that such language would work in St. Maarten and I’m not sure what could be alternative language.

There may also be no way to create the right message, and maybe instead of attempting to soften the blow, what both Greece and St. Maarten need to do is to speak some hard truths. In Greece’s case, the message may be to tell the people that extreme measures are needed to bring them back from financial disaster. In St. Maarten’s case, the message may need to be, “We cannot finance the developments we want to have, as fast as we want to have them, because our means don’t allow us to do so.

Donellis Browne